David Lim is one of the most successful Asian entrepreneurs in the world of wine. He was active since the market started, enjoying its growth, and he also witnessed the increasing number of consumers and their development. I have recently talked to him about what is happening on the market in the context of COVID-19, about the chances of Romanian wine in Asia, and about consumption habits in China. Although the discussion was conducted as an interview, I chose to present a condensed summary.

In 1999, David Lim was seen as “the crazy guy who opened a wine store in Malaysia, when no wine stores existed. It was a time when people enjoyed a sip of VSOP or XO or other spirits, but the only people who drank wine were seen as arrogant and snobbish. Despite that, the store was so successful that it started a franchise, and, in 2007, the Denise Wines network had 55 stores, making it the largest wine retail chain in South Asia.

Because the local food is spicy, the first wines to be successful here were those that could be paired with that, so a big Australian Shiraz was kind of a first choice, Lim explains. The early days of the Chinese or Malaysian wine markets bear a striking resemblance to the Romanian market’s same period – good wines mixed with Sprite, ice, or soda.

“To be able to consume such a combination, you need a wine rich in fruit notes and with high percentages of alcohol,” he adds. As a result, So the Chilean Cabernet, the Argentine Malbec, in general, and the American wines were the ones that were successful to the public. In fact, less educated wine consumers still prefer them. Still, in the past 15 years, the public became more refined and more sophisticated, so nowadays, they know how to appreciate a Super Tuscan or an Amarone.

So, the public is divided: newcomers with the New World wines, connoisseurs enjoying European classics… Where would the Romanian wine fit in? Or, for that matter, the wines from Moldova or other Eastern European countries? Lim thinks it may be difficult, but not impossible, and education is the key. “Those who want to try new wines, exotic, unknown wines, are consumers educated in the Cambridge spirit, who follow and listen to Robert Parker, Wine Advocate, or this kind of source.

It is difficult to enter such a market, it either takes a lot of education or you need a moment of sudden international interest, as it happened with the Tokay region. Still, it’s not impossible to enter this market, and Lebanese wine is a good example. No one knew such a thing existed, but it was successful. At some point, there was no five-star hotel or upscale restaurant without Lebanese wine on their wine list. But it took a lot of tastings and events…

A new wine on the market had no other chance than education. Or it may be a wine that makes you go ‘wow!’, for a good price, and a wine that makes the consumer want more”, explains Lim.

Regarding the prices, Lim expects a downwards shift in both producers’ prices and the market mechanisms. The main effects may be felt in China, where the state has a 50% tax on imported wine. Therefore, adding up the import taxes, distribution costs, and other associated taxes, as well as the addition of restaurants, a bottle of wine worth 8-9 Euros, ends up costing 30-40 Euros.

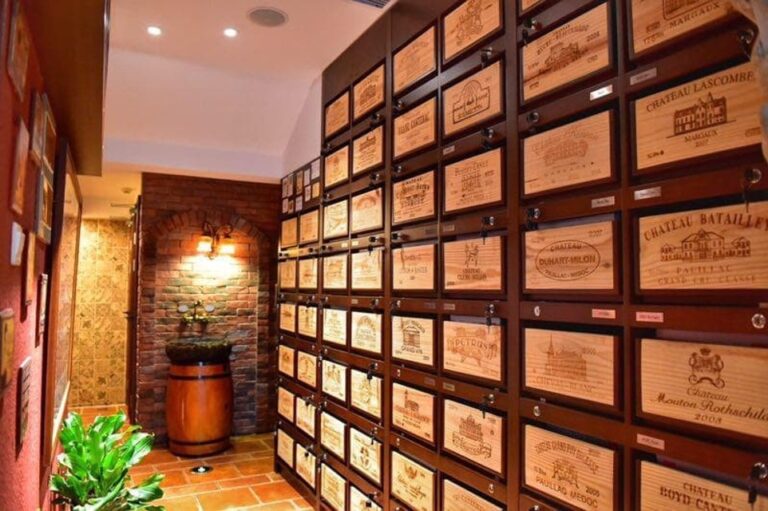

It is the reason why many Chinese feel ashamed to buy a bottle cheaper than 80-90 Euros when going out with their girlfriends or business partners. At least, for this price, they know they have ordered a bottle of decent wine. In fact, this aspect is one of Lim’s ingredients for a successful business. Selling from importers directly through the restaurant shortcuts the chain and makes wines more affordable.

In his French restaurant, Lim lists over 500 labels, and the Champagne Bar offers over 100 brands of bubbly. Add the wine stores, and it becomes apparent that people learned where to find a bottle of fine wine for a fair price. Even more of a deal, if Lim’s predictions come true: some major European producers already dropped their prices, and more are expected to follow the same trend.