Paraphrasing the titles of the western trilogy films about Transylvanians, I remembered that the French do not only dispute their supremacy with the Italians, in terms of gastronomy and wines, but also with the English, for their importance throughout history and their contribution to the formation of the English language. But it is less known how French wine, ah, so wonderful and untouchable by even a flower, has to do with… you guessed it, the English.

Well, let’s take it slowly. I remember how my high school French teacher used to tell us, with undisguised satisfaction and a broad smile, anticipating the terrible statement, that "English is a distorted French". Such an attack was then demonstrated by the numerous words that entered the English language through the French channel (see the film The French Connection, based on the homonymous novel by Robin Moore), some adapted phonetically, others preserved even today with the original pronunciation (e.g.: fiancé), other Gallicisms being attested in the 13th century (about 10,000), of which approximately 7,500 remain in the British language to this day.

If in the fight between the English and French etymons, it is even met the disappearance of the native lexeme, as for our favorite word, wine, it was assimilated phonetically, and the French vin(vẽ) becomes wine, while the vigne, vignoble becomes vineyard. Let’s not forget the universal terroir.

The English’s revenge

When you say France, previous experiences, general culture, clichés are activated, and in our minds, because we are greedy, aren’t we, gourmet dishes randomly parade by, butter, pastry with thousands of layers on top of which vanilla-flavored powders float and, of course, wines. The most famous region for wine lovers is, without a doubt, Bordeaux. Connoisseurs will continue to list, of course, Burgundy, the Rhone Valley, the Loire Valley, Champagne, and the most knowledgeable will mention Alsace and Languedoc Roussillon.

We stay in Bordeaux, to see what connection the English have with the region that gave the world a memorable wine and its nuance.

The story begins with the famous Richard the Lionheart, who, at just 15 years old, as a young Plantagenet offshoot, became Duke of Aquitaine. The English have not forgotten the year 1066 and the consequences of the Battle of Hastings. At least in the realm of wines, the English seem to have had a comeback.

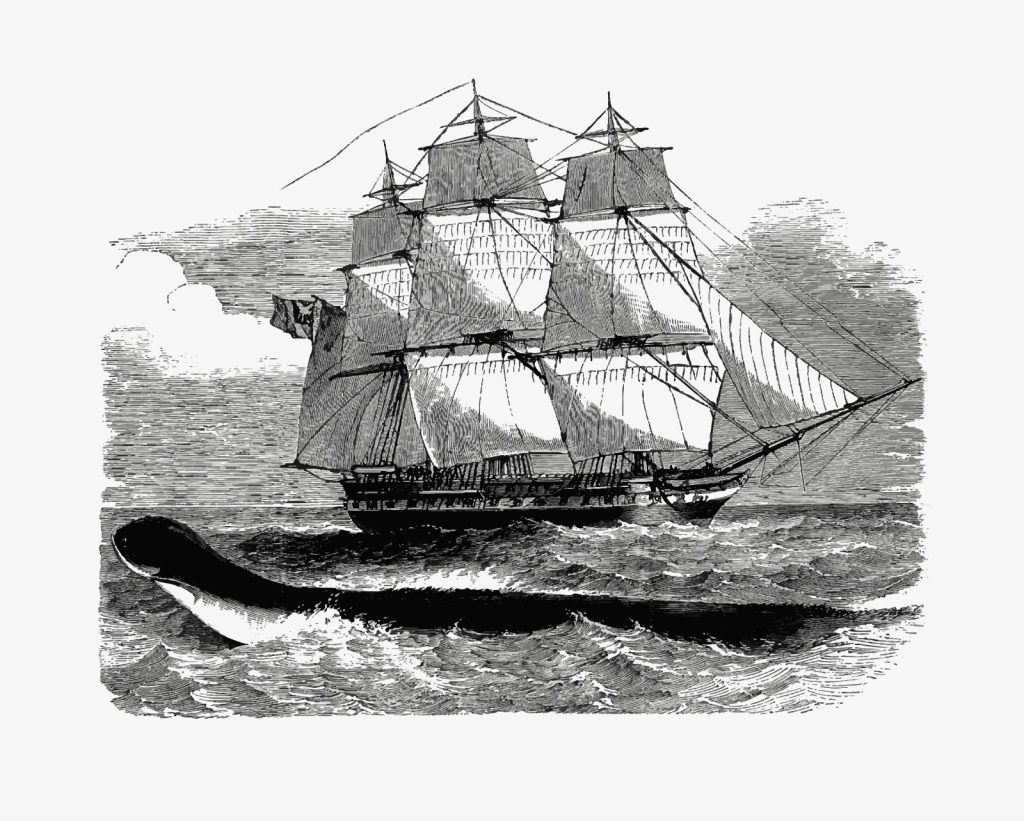

With the title of Duke of Aquitaine, the young Richard Plantagenet found himself with the southwestern part of France in his fermentable possession. Here a dark rosé wine was produced, which often bore the name Clairet. A few hundred years, from here, proud ships laden with Bordeaux wines crossed the English Channel to the English shores, because the once defeated had already caught the rich taste and saturated color of Clairet. And since such a revenge would not be complete without a proper invasion, thousands of castles were built by the English in this region, specifically to cultivate the vines and produce the much-coveted wines that brought joy and profit. The history of wines tells us that special ships were built at that time, capable of transporting large quantities of Clairet, but also other barrels. Anyway, the quays of Bordeaux were reserved for exporters of goods to England.

The Bartons and French Wine

Among the many owners of castles in the Bordeaux region, whose occupation is viticulture, is the Barton family. The members of the oldest family that has been dealing with wines continuously for hundreds of years are of Irish origin, the first being Thomas Barton, who arrived on the Normandy lands in 1722. A nephew named Hugh inherited the future profitable fortune, and after his association with Daniel Guestier, a famous company Barton & Guestier was born. After a series of adventures, the estate where they produced the wines became, through successive acquisitions, Château Léoville-Barton and Château Langoa-Barton, with the same fruitful collaboration between the Bartons and Guestiers.

This would be, in few words, the story of a famous Bordeaux wine with an inevitable Irish touch. Now, if we think about the infinite confrontation between the Irish and the English, we feel like quickly opening a bottle of wine, and pouring into glasses, let’s say, as Momo, a French cheesemaker, taught me: Santé, bonheur, sexe et bonne humeur!