Growing up in Șimleu Silvaniei meant, among other things, seeing in the spring, from afar, two or three pink spots on the Măgura hill, where the vineyards still kept their sap well-guarded in the roots embedded among the crystalline schists and in the wrinkled trunks, which did not dare to give a bud. They were the last almond trees. Spring was coming and with the beautiful weather, the vineyards also began to show signs of life. Many inhabitants of Șimleu cultivated vines on Măgura. Some obtained approval from the City Council of those times to clear a piece of land on the slope, which had been taken over by stubborn acacias, whose roots would not be pulled out easily. Others had inherited, despite the changes of government, at least part of the old vineyards, with houses and potbellied cellars, with guards who watched over the ripening of the bunches, carefully raking between the rows, the glassy sand resulting from the grinding of the shale. Any foreign step was identified, and the perpetrator was sought.

Well, among the proud vineyard owners was also Alexa Acsádi, whom her friends called Öcsi. On a steep slope, the path that passed dangerously close to a ravine, led you to the most beautiful vineyard on Măgura. With a southern exposure, the vineyard stood out from all the patches covered with vines of various varieties, especially hybrids, among which there were also a few noble varieties, such as all the vines from Acsádi’s vineyard: Riesling, Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Gris, Italian Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc, some Tămâioasă, some Fetească, and in the cellar, you were invited to a tasting. Having wine from Acsádi meant that the holidays would be grand.

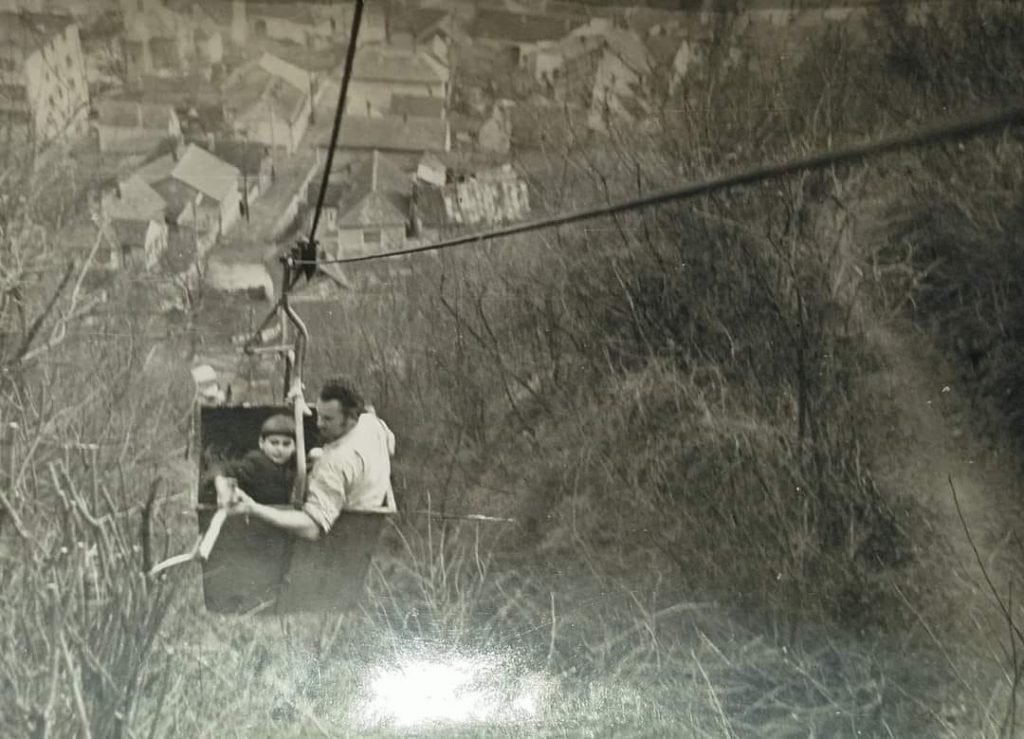

In individual households, the treatments were most often only with copper sulfate, while at Acsádi, there was talk of 7 different sprayings throughout the year. What is certain is that the bug had gone. The winemaker was a master carpenter by trade at the “Simion Bărnuțiu” High School and in those days, in the high school workshops, the school furniture was produced, but they also wove carpets by hand, and they did tailoring, so Mr. Acsadi invited his craftswomen once a year for a glass of wine. He had also grown old, and so had the craftswomen. In order to be able to carry the necessary materials up to the vineyard, Alexa Acsadi installed a funicular, using a mine cart, which only God knows where he had obtained. What is certain is that everything that the tall man, who had been Öcsi baci, could no longer carry on his back, was now transported by the funicular, powered by electricity. That is how the craftswomen climbed, whose years and extra pounds were no longer helping them climb the hill.

But the improvised funicular proved its usefulness especially when, from Zalău, the residence of Sălaj, representatives of the party county arrived with comrades from Bucharest. After visiting several economic objectives, the route necessarily included Acsadi’s vineyard, where the house specialties were tasted. The wine was so good that the visitors were in danger of losing their bodily integrity, so the descent from the vineyard was no longer done on foot, especially since the nights were a bit dark, but by funicular. I did not find out how many paths the tasters took after descending from the funicular that swayed shamelessly over the ravine. What is certain is that after the revolution, the new generation of politicians spent time at Acsadi’s vineyard, whom no one asked about the funicular for which Alexa Acsadi had been criticized, before 1989, in the newspaper Scânteia.

I climbed Măgura highs and I didn’t tell you any lies.

Photo source: Sălajul pur si simplu.